Capturing Wilderness: The Photography of QT Luong

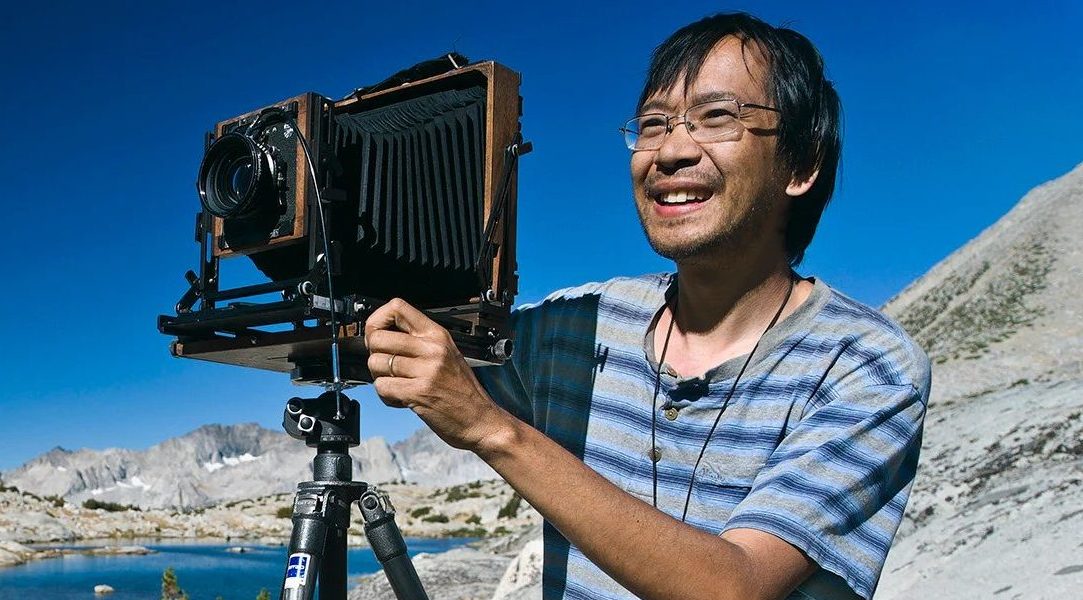

QT Luong is a wilderness photographer with an impressive body of work featuring America’s public lands. One of Luong’s most well-known accomplishments is being the first to photograph all 63 U.S. National Parks with a large format camera. Born in Paris, France to Vietnamese parents, Luong quickly fell in love with America’s unfamiliar wild territories when he moved to California to work as a computer scientist for UC Berkeley in 1993. Since his renowned work in the national parks, Luong started a new project: an exploration of America’s national monuments. His most recent photography book, Our National Monuments: America’s Hidden Gems, invites readers to discover and experience spectacular and less traveled public lands.

All Roads North had the honor of asking Luong a few questions about his adventures in America’s lesser-known wilderness spaces:

ARN: After having visited every national park, what surprised you most about the national monuments?

QTL: I was surprised to find the national monuments managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) to be so wild, with even fewer facilities than I expected. With the exceptions of national parks in Alaska and a few island parks, when you visit even the lesser developed national parks, you are guaranteed to find paved roads, trails, a visitor center, and restrooms. Some of the national monuments are entirely devoid of such basic facilities. Sometimes, there is so little signage that you don’t even know you’ve entered the national monument.

Why do you think it’s important to explore lesser-known national monuments, or as your book refers to them: “America’s hidden gems”?

First, you have to understand why those national monuments are important. The 22 land national monuments in the book cover a significant portion of the American landscape, totaling about 11 million acres. They represent a broad cross-section of natural environments, from deep canyons to high mountains, from cactus-covered plains to conifer forests, and from deserts to lush river habitats. For comparison, the 51 national parks in the contiguous United States total about 19 million acres. The marine national monuments are another order of magnitude, totaling 218 million acres. Besides their vastness and diversity, the monuments under review hold natural and historical treasures that rival those found in our beloved national parks. Almost half of our treasured national parks started as national monuments, so in some sense, they could be viewed as future national parks.

We conserve only what we love, and we love only what we understand. However, the general public is not aware of the national monuments. There is nothing that brings better understanding and connection than a visit. The more adventurous setting of the national monuments results in much lighter visitation, even though you can often find similar subjects and environments as in the nearby national parks. The national monuments offer the opportunity to discover lands out of the beaten path, free of crowds and of the strict rules of the national parks. This may not last forever. When Ed Abbey was a ranger at Arches National Monument and wrote his seminal Desert Solitaire, there was just a single dirt track leading into the monument. Last year, on several days Arches National Park had to close to further entries early in the morning due to overcrowding, and this year visitors will need to have an advance reservation to enter the park on a timed entry system.

Which national monuments were particularly memorable to you?

Each of them represents such a unique environment and different experiences that it is difficult to pick favorites, so where to start? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is so vast and so diverse that one could spend a lifetime exploring it. Maybe I’ve developed a deeper relationship with it than with the other monuments since I’ve visited it since it was established in the mid-1990s. On each return trip, I always find new places to explore.

On the other hand, I had heard of, but not visited Upper Missouri Break National Monument until I started the project that lead to Our National Monuments. The visit was a special experience because whereas one visits the other monuments by driving and hiking, there I went on a four-day paddle trip along the Upper Missouri River. Floating at a slow pace, I connected with a time when the landscape of the West was wild, seeing little change since the days of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and finding remarkable geology that I did not expect in this part of the country. Then there is Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument for its incredible remoteness and views of the Grand Canyon, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument for the otherwordly rock formations, Bears Ears for the treasure trove of ancient dwellings…

Your book makes a passionate case for conservation of these places…what do you see as the major threats and how can people help?

When the previous administration conducted the review of those national monuments in 2017, and subsequently dramatically reduced in size Bears Ears and Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, it was with an eye toward opening the door to industrial development and extraction. As citizens of this land, the voice, and votes of each of us count. The change of administration in 2021 brought for the first time a Native American to a cabinet position, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. One of her first actions was to visit Bears Ears and Grand Staircase National Monuments and recommend the restorations of those two national monuments to their original size, which President Biden did on Oct 8, 2021. However, the threats have not gone away. The Republican politicians in Utah have not accepted the restorations and are preparing legal challenges. We should remember John Muir’s appeal that “the battle for conservation will go on endlessly.” We can no longer take designations for granted. As citizens who care for lands that belong to all of us, we need to remain vigilant and involved.

You’re known for favoring using a large-format camera– Was this the case for the National Monuments project? Why?

The book includes a few images made with the large-format camera from the 1990s, but I photographed this project mostly using digital cameras. The technical quality of the images they are producing has been steadily improving and is now close to the large-format film, and they offer much greater practicality and versatility while reducing the environmental impact if one photographs a lot.

You’ve spoken about Ansel Adams being a huge inspiration in the beginning of your career– which contemporary photographers inspire you?

David Muench’s body of work is unrivaled in the field of nature landscape photography. He made great photographs before I was born and is still active today.

What are you working on or excited by right now in your photography work?

I am mostly known for scenic landscape photographs of the national parks, but I have been working on a number of series that bring either different perspectives or more conceptual approaches to those places. With Our National Monuments, I have moved from national parks to lesser-known lands. I am now looking at even more hidden wild places that are not protected yet as national parks nor national monuments.